We watched the eclipse at the Fort Kaskaskia State Historical Site in Illinois. This is atop a high bluff overlooking the Mississippi River. It is the same place my daughter and her family saw the 2017 eclipse (my wife and I saw that one in Nebraska), so it was their second experience of totality in the same place!

Our tentative plan all along had been to go to Fort Kaskaskia. I had been watching weather forecasts and models for quite some time, even before I left home in Colorado six days before the eclipse. Generally, the forecasts came into agreement that there would be only high, cirroform clouds at the time of the eclipse. But the models disagreed on how much of the sky they would affect, and how thick they would be was also uncertain. Usually, these clouds are thin enough not to be much of an issue for viewing an eclipse, but they can occasionally thicken enough to obstruct the view. The STL office of the National Weather Service expressed a fair amount of uncertainty about the the thickness, while the PAH office was more optimistic that only thin clouds would be likely. Fort Kaskaskia is in the STL area of responsibility, but near the boundary with the PAH area just to the east and south. We never really wavered from heading to Fort Kaskaskia, but did keep open the possility of making a last ninute dash to the southwest or northeast if it looked like thick coulds would be over that location but other areas along the path of totality within reasonable driving distance would be unobstructed. As it turns out, Fort Kaskaskia was perfect, wtih only scattered thin cirrus clouds - not an issue for viewing the eclipse at all.

Another element of uncertainty was traffic. We knew that a lot of people from the St. Louis area and others from all over would be heading from there into the nearby path of totality the morning of the eclipse. We debated different routes, but based in part on online travel time estimates, decided to take I-255 to Illinois route 15 which would connect us to Illinois route 159 on the south side of Belleville which would take us south to Red Bud, from which we would continue south on Illinois route 3 to Fort Kaskaska. We left my daughter's home in Edwardsville around 8 a.m. to take this route. This worked very well, with only one slight backup at Red Bud, but basically we got to Fort Kaskaskia in the normal driving time of about an hour and a half, plus a pit stop at a convenience store in Red Bud. Although we had totally manageable traffic, my daughter saw online that there was a 25-mile backup on southbound I-55 south of St. Louis in Missouri. In fact, I later heard that this backup was so bad that some people taking that route did not make it to the path of totality. More on the traffic aspect later. But this confirmed to me what at least three different people told me - the traffic would not be nearly as bad on thie Illinois side because a lot of Missouri people do not even think about going into Illinois. They seem to think it is farther away than it really is.

There were quite a few people at Fort Kaskaskia, but per my daughter and son-in-law, not as many as there were for the 2017 eclipse. We found a good viewing spot at the lookout - at the top of a high bluff over the Mississippi River, looking to the west or WSW across the river and over Kaskaskia Island, which is open flat bottomland across the river, but still in Illinois due to a long-ago shift in the river channel. It is no longer truly an island, though it once was, but keeps the name.

We were there by around 10 a.m., and staked out our spot near the northwest corner of the large picnic shelter, setting up our lawn chairs and spreading out a couple blankets. I set up my main camera, a Canon DSLR with a 70-300 zoon lens and a solar filter that screwed onto the lens. In my first total solar eclipse in Nebraska in 2017, I mostly concentrated on watching the eclipse - did not want to miss that experience fussing with the camera. I did take some pictures during totality with the same camera and lens, and one of them somehow came out pretty decent, even though I decided not to fuss with a tripod, partly for the reason noted above and partly due to the high sun angle, which made using a tripod more difficult. It would be a high sun angle again this time, but I decided that, since this was not my first total eclipse experience, this time I would concentrate a little more on trying to get good pictures. And with a much better solar filter, I would be able to get pictures during the partial phases leading up to totality. I made limited efforts at this in 2017, and had even more limited success. Getting the sun in the frame almost fully zoomed in and getting the focus correct took longer than I had anticipated - probably a half hour or so all told - but I did finally succeed and took a couple pictures of the sun with the solar filter before even the partial phases of the eclipse began. It seemed to work, so all I would have to do now is make minor shifts in the aim of the camera to keep up with the sun as it moved across the sky. This was not as difficult as I thought it might be, as long as I made these shifts frequently and regularly. So, I figured I was ready.

My daughter had packed a cooler with lots of food for lunch, and we bought water and more ice at our stop in Red Bud. Despite the rather large number of people there, there were plenty of tables available in the large picnic shelter, and not everyone was eating at the same time. So we were able to enjoy a nice lunch in shade, with no rush since we had arrived more than two and a half hours before the partial phases of the eclipse began. Some people had pretty elaborate lunch/tailgate setups, with grills and hot food and even in one case, champaigne. We weren't that fancy, but had a very good lunch.

Also while we were waiting for the eclipse to begin, I had a pleasant visit with fellow storm chaser Scott Kampas from St. Louis, and some of his friends who were camping at Fort Kaskaskia for the eclipse. Scott and I had found out through Facebook messaging a week or so earlier that we both tentatively planned to view the eclipse at Fort Kaskaskia. So I guess you could say we had chaser convergence at the eclipse - the good kind, for sure!

The day of the eclipse was the warmest in some time in eastern Missouri and southern Illinois. When I got to Edwardsville the previous Thursday, the temperature had struggled to get out of the upper 40s. The day before the eclipse, there were supercells in parts of southeast MO and southern IL ahead of a dryline that moved through the area, strong enough to produce 1-inch hail and wind damage in the area around Lake Carlyle. One of the storms even got a tornado warning. Update - The St. Louis National Weather Service has confirmed that the storm did indeed produce an EF-1 tornado, with a path length of about a mile and a quarter, that began about 3 miles northeast of the north end of Lake Carlyle. This was based on a damage survey done the next day, i.e. the day of the eclipse. I do hope the meteorologists that did the survey were able to take time to see the eclipse, with which totality did occur over the southern part of Lake Carlyle. Here is a picture I took from Edwardsville of the cluster of supercells that produced the tornado. The storm was about 50 miles away when I took this picture.

Behind the dryline on the day of the eclipse, the air was much drier, but even warmer. By mid-day, just before the eclipse began, the temperature had risen to near 80. In fact, it so heated the surface that numerous dust devils began to form on the flatlands of Kaskaskia Island, across the Mississippi River from our viewpoint, below us to the west/west-southwest. Scott noticed them first. There were a number of them in the hour or so before the eclipse began, probably 10-15 at least, maybe more. I did not want to disturb the camera I had set up for the eclipse, which would have been ideal for photographing the dust devils a mile or so away with its 70-300 zoon lens, but I did have another DSLR with an 18-55 lens, so I used that and later cropped the best picture I got. I thought it turned out pretty good:

These continued up until the beginning of the eclipse, but stopped pretty quickly once it was under way and the surface temperature began to cool, reducing the lapse rates/instability near the surface.

The partial phase of the eclipse became evident around 12:45 p.m., beginning with a tiny indentation as the moon began to impinge on the lower right portion of the sun. I regularly took pictures with the solar filter as the moon gradually moved upward and to the left over the sun, obscuring more and more of it. By about 5 minutes before totality, the temperature had dropped noticeably, and lots of bugs suddenly appeared and seemed to suddernly be everywhere. This was the only anomalous animal behavior I noticed. Interestingly, this was much the same as what we experienced in the 2017 eclipse in Nebraska. A couple minutes before totality, my daughter pointed out the shadow of the moon rapidly approaching from the southwest. One thing she had liked about Fort Kaskaskia during the 2017 eclipse was that from the high spot on the bluff above the river, they could see the approaching darkness. This time, the shadow darkened the ground in the distance across the river, the sky in the southwest became very dark, and the dusky pinkness like you see just after sunset was very noticeable in the northwest. And the darkening light created a very eerie sensation. Since the DSLR I had used for the dust devil was now equipped with a mylar solar filter, I grabbed my cell phone and snapped this picture:

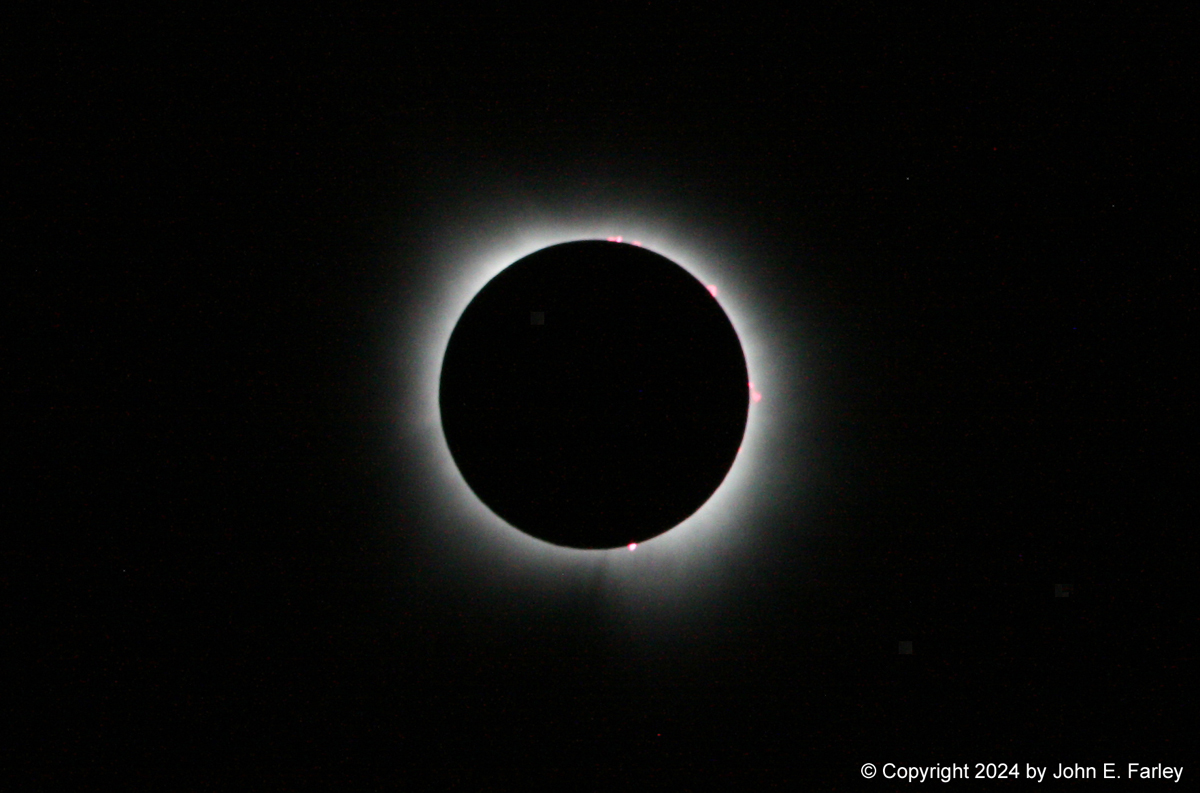

Naturally, the phone tried to compensate for the low light and made the picture much brighter than it really was, but with some post-processing, I was able to get it back pretty close to how it really looked. Not perfect - the land and sky in the southwest were darker than in the picture above - but pretty close. That picture was taken about a minute before totality. Once totality arrived, I quickly got the solar filter off the camera on the tripod with the long lens, checked the focus, and started getting pictures. This one was my favorite:

One thing I love about this picture and others I got during totality was that you can clearly see solar prominences at several locations at the top, bottom, and right side. The camera even picked up the pinkish-orange color of the prominences. We could not see these with our naked eyes. Not surprising with my no-longer-so-good 74-year old eyes, but my daughter, her husband, and my granddaughter did not see them either. But they certainly clearly show up in the photos. Here is another wider-angle version of this photo, probably closer to how the eclipse actually appeared to us:

Like I said, I concentrated more on photography this time than in 2017. At one point early on, probably while I was taking off the solar filter and checking the focus, there was a very audible reaction to something from the crowd. I soon realized this was because a jet flew across or very near the eclipse - afterwards I could see the contrail to the right of the eclipsed sun. Despite this, I did take some time to just watch - a must during a signt as amazing as a total eclipse. I think my biggest reaction was a realization of how different this eclipse was from the 2017 eclipse - more on that below. But it did make me understand why some people go to so much trouble to see them over and over again. My former dean at SIUE and her husband travel all over the world to see them and have seen something like 25 or 30 total eclipses. It took my second eclipse to understand why.

One thing I was hoping for with this eclipse was to get a picture of the "diamond ring" - a bright spot of light that occurs for a second or two at the beginning and end of totality. I was ready with my finger on the camera button this time, and when it appeared, I immediately snapped a picture. Wasn't sure at the time whether or not it worked, but turns out it did:

Something I like about this picture is that, despite the brightness of the tiny piece of direct sunlight that makes the diamond effect, you can still see at least two prominences, one or two near the bottom and one above the diamond.

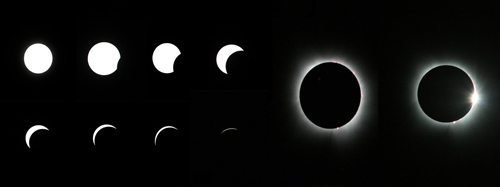

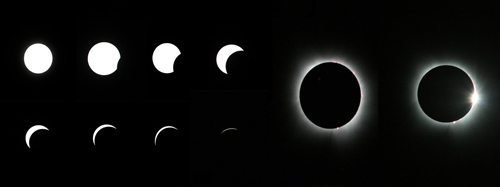

As I mentioned, this time I had a better solar filter to use with the camera with the 70-300 mm zoom lens, so I was able to photograph the partial phases of the eclipse effectively. Here is a collage I made of the progress of the eclipse from before it began up to the appearance of the diamond ring at the end of the eclipse:

At least where I experienced them, the 2017 and 2024 total solar eclipses had several noticeable differences:

1. The visible corona was much larger and less uniform, and probably brighter, in 2017. The corona in the 2024 eclipse did not visibly extend nearly as far from the sun, and was more uniform in how far it did extend. The 2017 corona had three distinct points, one more or less straight up and another pointing upward and to the right. The third one pointed downward and to the left, alligned roughly with a line that would have passed in the center between the two upward ones. The 2024 corona, in contrast, was much more round, more like a ring around the sun that faded as it got farther from it, but not extending nearly as far from it as the one in 2017. It also did not seem quite as bright as the corona in 2017.

2. It was noticeably darker with the 2024 eclipse than with the 2017 eclipse - felt more like night. I suspect both this difference and the one in the size and perhaps brightness of the coronas are because the moon was closer to earth in the 2024 eclipse (also accounting for the longer time of totality in 2024), and thus let through a little less of the light from the corona. But some of the difference may also be tied to differences in the solar cycle, at a high point of activity in 2024 and at a low point in 2017.

3. No doubt due to this difference in the solar activity cycle, there were no prominences visible in 2017, but there were several in 2024. Nobody in our group saw the prominences with their naked eye (though I heard some people did), but they were clearly visible in all of my photos (taken with a 70-300 zoom lens, almost fully zoomed in at a focal length of 270 mm). Even in the picture of the "diamond ring" at the end of totality, there are still some prominences clearly visible. And I am sure they could be seen with any good telescope or binoculars.

Here is a photo comparison of the two eclipses:

Undoubtedly this slightly exaggerates the differences, because I know I got the 2017 picture a little overexposed, and the 2024 one could be slightly, to a lesser extent, underexposed. But the differences in the size and shape of the corona and the darkness of the sky were real and, at least to me, quite noticeable without any camera artifacts.

As I said earlier, since this was my second total solar eclipse. I concentrated more on photography this time, and I am also better now with my camera settings than I was in 2017. As a result, I did better this time, and was pleased to have been able to capture both the prominences and the "diamond ring."

I mentioned earlier that there was a noticeable temperature drop. It began a while before totality, as the majority of the sun became blocked. Before the eclipse began, it was hot to be out in the direct sun, but by the time that the majority of the sun was blocked, that was no longer the case. In fact, nearby weather stations in both Cape Girardeau, MO and Carbondale, IL recorded 9-degree temperature drops during the eclipse. Even in St. Louis, which was not in the path of totality, there was a 4-degree drop. Scott had mentioned to me before the eclipse that the HRRR forecast model was predicting the temperature drop. I had heard that the majority of forecast models were not able to take the effects of the eclipse into account, but clearly that one did. Another interesting thing is that while, as I mentioned, bugs appeared and were everywhere just before totality, by the time totality ended, they were gone. Several people who were at the same location for the 2017 eclipse mentioned that cicadas got very loud right before totality that time, but this time, it was too early in the year for cicadas, so that did not happen.

Remembering the traffic tie-ups both in Nebraska and Illinois after the 2017 total eclipse, we decided to collect our stuff and start leaving around 15 minutes after totality ended. There certainly was more traffic on our route, along with some back-ups, after the eclipse than before, but nothing too bad. There were people directing traffic at the park entrance, and when we got back to IL route 3, people politely alternated, allowing those of us entering from the road to the park to turn left without a big wait. The largest backup was at Red Bud, where there is a 4-way stop at the center of town where state highways from the four directions meet. Strangely, there was nobody directing traffic there, so it backed up for probably somewhere between a half-mile and a mile. But despite that, we were back in Edwardsville in 2 hours, only about a half hour more than it would normally take. That was around 4:30. We went out to dinner around 6:30 and had an excellent dinner at Bella Milano. Later, as I watched the 10 p.m. news, I was startled to see live shots of an ongoing massive backup of traffic on I-55 south of St. Louis of people trying to get back to St. Louis after the eclipse. I also heard there were big backups of traffic trying to get back to places in central MO like Jefferson City. So basically I-55 and at least some other roads in MO were massive nightmare parking lots both before and after the eclipse, while we had no trouble at all on the Illinois side. As I mentioned, I even heard that there were people who were unable to get into the path of totality because they were stuck in the mess on I-55. Fortunately, by taking the less travelled roads on the Illinois side, we were able totally avoid that.

Total travel distance for this trip: 2,640 miles.

Return to 2024 Weather Observation Page